Raleigh Tavern Architectural Report, Block 17 Building 6AOriginally entitled: "The Construction of Raleigh Tavern: A Brief Report on its Eighteenth Century Development"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report series - 1624

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

The Construction of Raleigh Tavern

A Brief Report on its Eighteenth-Century Development

Department of Architectural Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

December 31, 1989

Introduction

Acting on a request from the Department of Collections, several members of the Architectural Research staff convened to consider the eighteenth-century construction sequence at Raleigh Tavern. Our deliberations were limited to the main building as it appeared in the eighteenth century, except when exceeding those bounds promised to illuminate earlier events. Preliminary conclusions were afterward relayed verbally to the curatorial staff, anticipating the preparation of a formal report when time permitted. This written report incorporates certain changes in our thinking which have developed since that time. These changes should not materially affect the furnishing scheme previously proposed by the Department of Collections on the basis of our preliminary information.

The Archaeology

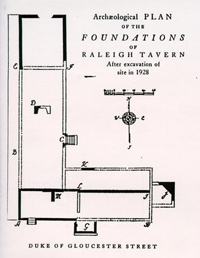

The archaeological evidence is of central importance to this discussion, but because no archaeological report was completed for the main building, we were obliged to rely on Rutherford Goodwin's 1936 guidebook, The Raleigh Tavern, for an overview of the archaeology and how it was interpreted at the time of reconstruction (Figure 1). According to Goodwin, the east end of the Raleigh--the present passage and billiard room--was the earliest portion to be built. Second in the sequence was that unit which now encompasses the two front rooms on the west side of the passage. Next, by Goodwin's account, came the Apollo/Daphne Room wing, and last of all came the large room appended to the north end of this wing.1

The actual building sequence may have been somewhat different. We believe that the western portion of the tavern--not the east--constituted the initial phase of construction. The evidence for this conclusion is laid out below.

Period I

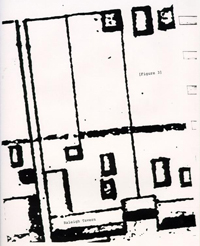

The foundation wall which once separated the east and west parts of the building constitutes a critical piece of archaeological evidence, since it once served as an end wall of the period I structure. Was this first-period wall bonded into the east or west portion of the foundation? The archaeological plan is inexplicably silent with regard to this crucial question (Figure 2). Although much of the original brickwork was retained in the reconstructed cellar walls, remaining fragments of the cross wall were dismantled. As a result, our conclusions must be drawn from photographs of the excavations. While the evidence cannot be regarded as conclusive, detailed examination of these photos persuades us that the all-important wall belonged to the west end of the building. The cellar walls were 1-½ bricks thick, laid in English bond. If the corners were built with a ¾ bat backing up the closure, a toothing of about 2" would have resulted on the 3 interior angle of the intersecting walls--precisely the condition visible in the photograph where the cross wall meets the western section of the north foundation wall.2 It follows, then, that this western portion of the tavern constituted the first phase of construction, and that the eastern half of the building was a period II addition.

But even if the photographic evidence is discounted, there is still cause to question Goodwin's explanation of how the Raleigh developed. Since the west section of the building was the deeper of the two components, the east structure could have butted cleanly to it. The west building, on the other hand, makes little sense as an addition, since it would have joined awkwardly to the narrower east building. Again, the west section seems to be the earlier of the two structures.3

The reconstructed interior layout of the Raleigh offers further support for this conclusion. York County records indicate that Henry Bowcock was keeping tavern on this site by 1717. At this early date, the tavern had not yet emerged as a distinct building type. Architecturally speaking, there would have been little to 3 distinguish Bowcock's public house from a dwelling house. Regardless of how it was used, the period I section of the Raleigh was almost certainly domestic in character. In the context of what we know about domestic building in this period, the eastern half of the building--the passage-and-billiard room unit--makes little sense as a stand-alone element. Though several one-room houses with side passages are now extant in Williamsburg, only two of these date from the eighteenth century. The earliest of these was probably the Benjamin Waller house--the result of an eighteenth-century addition. Only the Lewis House appears to have been built as a side-passage, single-room dwelling. It may date from the middle of the eighteenth century.4 Significantly, none of the early 4 eighteenth-century inventories known to us describes a house of this kind. The elongated plan of the billiard room, moreover, deviates considerably from the nearly square proportion observed in the main room of most eighteenth-century Virginia houses. Even the usually long first period room of the Waller house falls considerably short of the Raleigh's present billiard room in terms of length/width ratio.5 The first phase of the Raleigh must make sense as a discreet building. The eastern portion of the structure fails to meet this test convincingly.

The western end of the building, embracing the two front rooms on the west side of the passage, does meet the test. The westernmost room is roughly square in proportion--the other is a 5 fraction less than square. This accords perfectly the proportioning typically observed in hall/chamber dwellings of the period. As in some earlier houses of this sort, these two rooms were served by a single, centrally-located chimney. Here, archaeological evidence clearly indicated the existence of corner fireplaces in each room. In the context of local house-planning tradition, this unit makes complete sense, being a center-chimney, hall/chamber building, later expanded by the addition of a passage and a large public room--a process of extension similar to that later carried out at the house of Peyton Randolph.6

Period II

If the period I status of the Raleigh's west end is granted, the consequent building sequence accounts in a historically coherent way for the entire street-front portion of the building, stretching a single file of rooms across the entire width of the lot in two successive periods of construction.

The tavern may have reached this period II form in 1733-35 when housecarpenter James Wray completed carpentry work valued at more than £47. (That this sum involved a substantial building is clear when we consider that in 1708 Jean Marot paid only £50 for 6 what is now the west end of Shields Tavern). Other work performed by Wray at the Raleigh included 30 squares of shingling and 780 yards of interior painting.7

To cover the interior wall surfaces of the period I and II structures would have required approximately 743 yards of painting--a figure that correlates closely with Wray's account. Assuming a roof slope of 45 degrees, though, only about 17 squares of shingles would have been required to cover both the east and west ends of the building.8 The remainder might have been used to cover outbuildings or perhaps the northernmost room of the tavern which may have once existed as a detached structure. (See discussion of North Room below). This latter structure would have required about 10 additional squares of shingling, bringing the total to 27 squares--about 3 short of the 30 squares mentioned in the Wray account.

In any event, it is clear that the period I west structure alone cannot account for the work completed by Wray 7 between 1733 and 1735. In all likelihood, this period saw construction of the tavern's east end.

Period III

Next in the sequence came the rear wing which embraced the Apollo room (along with its adjoining passage) and perhaps the space known as the "Daphne room."9 Significantly, the first known reference to the Apollo Room appears in the 1751 diary of John Blair--just prior to the first indications of a "Great Room" at Wetherburn's tavern in 1752.10 It may be that the wing was built shortly after Alexander Finnie's purchase of the property in 1749. Together with construction of the Governor's ballroom wing early in the 1750s, the addition of these public rooms to the town's two largest taverns, marked a mid-century "building boom" which coincided with the decision to rebuild the burned-out Capitol after its destruction by fire in 1747.11

The Problem of the North Room

The large room at the north end of the rear wing poses a special problem in regard to the construction chronology. Archaeological documentation in the form of a clean corner shown on the Knight plan suggests that the north end of this rear wing was built against an existing structure, which was about 8 inches wider than the addition. However, photos of the excavation show only a void in the foundation wall where one would expect to see this corner. It is possible that remaining fragments of this corner were pulled out after being recorded, or that Knight's drawing represents his reconstruction of earlier conditions, based on decayed physical evidence. Because the photographs are inconclusive, it seems best--in the absence of other evidence--to accept Knight's interpretation of the physical remains and all it implies for the construction sequence and interpretation of the building.12

9Granting Knight's depiction of the foundation, it is difficult to establish the construction date of this space other than to suggest it was built prior to period III, when the foundations of the rear wing were laid against it. The space may have functioned as a tenement or perhaps as a billiard house.13

Period IIIa

During or soon after construction of the Apollo/Daphne extension, a shed was added across the back of the tavern, adjoining the east wall of the new rear wing. This shed was almost certainly in place by 1770 when appraisers inventoried the contents of Anthony Hay' s estate. Although individual rooms were not called out by the appraisers, discreet spaces are implicit in the pattern of listing the building's contents. The curatorial staff suggests that there were at least three rooms in this shed, and that the 10 present porch was, in fact, an enclosed space. Architecturally, this would be more in keeping with the sorts of additions typically made to the rear of early buildings in this region.

Period IV

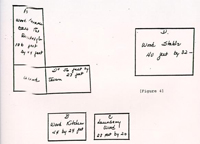

The chronological relationship of this new shed to the small room situated off the northeast corner of the building is problematic, as the junction of the two foundations was destroyed by construction of the nineteenth-century commercial building that succeeded the Raleigh on this site. Though Mrs. Timberlake appears to have mentioned no shed rooms in her recollections of the building, she did refer to the northeast extension as a "ladies' withdrawing room."14 And though the shed foundation was almost entirely obliterated, the underpinnings for this added room, intruding into the shed space, remained nearly all intact. Moreover, the Frenchman's Map seems to include the northeast room, but not the rear shed, in its depiction of the tavern (Figure 3). In the light of these facts, it would at first appear that the northeast extension post-dated demolition of the shed.

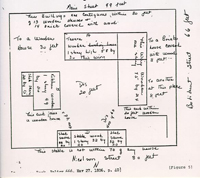

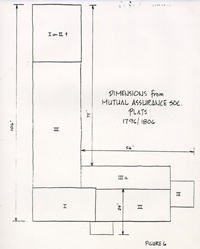

But plats of the property and buildings made in 1796 and 1806 by the Mutual Assurance Society offer some interesting clues 11 of the shed's exact nature and continued existence. (Figures 4 & 5). The Mutual Assurance plats are notorious for their inaccuracy but in the case of the 1796 document, the agent seems to have measured his building with a remarkable degree of accuracy. The dimensions given for the rear wing of the structure--106 x 24 accord exactly with the actual building, if the depth is measured across the north end of the wing (Figure 6). This exactitude suggests that remaining measurements should accord with the building as well. From the markings of the plat, it is clear that the front portion of the building was measured from the east wall of the rear wing to building's eastern extremity. Significantly, the agent's dimension of 56 ft. makes sense only if the northeast extension is included. The actual measurement is 56 ft. 6 in. Again, the accuracy of the agent's measurements is remarkable. More revealing, though, is the measured depth of this front portion of the building. The agent's dimension of 23 ft. is 4 feet off the mark if measured from the street facade to the rear of the shed. It fits perfectly if the measurement is taken from the back wall of the billiard room to the front face of the nineteenth-century porch piers shown on Knight's archaeological drawing. (The inclusion of this structure in the agent's dimension may indicate that it was at least partly enclosed at the time.)15 The apparent 12 exclusion of the rear shed in this measurement suggests that it was either gone or that it had become, by this time, an open structure.

The latter was probably the case, for the second plat, made in 1806, suggests that the shed did survive in some form. In this instance, the agent's dimension for the length of the rear wing--75 ft.--seems to make sense only if the measurement is taken along the east side of the wing, beginning at the rear shed. (The actual measurement is 78 ft. 6 in.)16

The shed seems to have existed as an enclosed space as late as 1770 when the Hay inventory was made.17 It is likely that the northeast room was erected sometime between that date and 1782 when the room appears on the Frenchman's Map. This may be the "New Room" referred in Humphrey Harwood's 1786 account for work 13 performed at the Raleigh.18 The closed shed evident in the 1770 listing of Anthony Hay's estate, may have been opened up to create a porch at the time this room was added. As a result, the present arrangement seems plausible for the period of the 1780s.

In 1782, the Frenchman's map also depicted a sizable porch running across the front of the tavern. This too was a late eighteenth-century addition, predating the enclosed porch later measured by the agent. A second line of square piers, aligning perfectly with the front of the stoop foundation, was probably associated with this earlier structure.

Additional Observations - The Second Floor

As reconstructed, the roof framing of the billiard room and the back porch is an integral unit, spanning from the front 14 facade of the building to the rear plate of the porch. When we consider that the shed (or porch) was probably built about 15 years after the tavern's east end, it becomes clear that the roof over the front portion of the tavern would have constituted an independent unit, with the shed rafters framed against its rear slope in the typical manner. This observation would at first seem to invalidate the reconstructed second-floor plan for the front section of the building. This reconstructed arrangement almost certainly reflects the following considerations:

- 1)A desire to avoid having the roof of the wider rear wing show awkwardly above that of the front.

- 2)A desire to eliminate the problematic junction of chimney and roof planes which would otherwise have resulted where the rear wing joins the front of the building.

- 3)The need for a usable second floor. Owing to the unusually short depth of the building, the original ceilings seem to have been scarcely six feet in height. Such rooms seem incomprehensible, but at Pine Slash, in Hanover County, a person 6 feet or more in height cannot stand up straight in the well-finished second-floor room of c. 1800.

One might defend the current arrangement by suggesting that construction of the Apollo/Daphne wing and the rear shed prompted Finnie to expand the second floor of the tavern as a means of resolving the very difficulties enumerated above. Significantly, the curators, having studied the sequence of the Hay inventory, suggest that nine curtained bedsteads were located on the upper floor--a fact with clear architectural implications. Further 15 analysis of the Lossing view and Humphrey Harwood's accounts for whitewashing the Tavern--exercises which fall outside the scope of this brief paper--might assist in resolving the question.

Summary Chronology

Tentatively, then, we would summarize the eighteenth-century construction chronology of Raleigh Tavern as follows:

| Period I | Construction of hall/chamber unit which now comprises the west end of the Raleigh, possibly after Thomas Jones acquired lot 54 in 1716. |

|---|---|

| Period II | Addition of spaces now referred to as the south passage and billiard room--in 1733-1735. This completed the street-front portion of the building |

| Period III | Construction of the rear wing--the north end of this addition was joined to an existing building--probably a tenement or billiard house erected during period I or II. Construction of the wing may have occurred shortly after Alexander Finnie's appearance on the site in 1749. |

| Period IIIA | Addition of the back shed, adjoining the east wall of the rear wing. (This may have been carried out concurrent with construction of the rear wing in period III). |

| 17 | |

| Period IV | Addition of northeast room referred to in the nineteenth century as the "Ladies' Withdrawing Room." This occurred sometime shortly before 1782 when it was depicted on the Frenchman's Map. Indeed, this was probably the "New Room° mentioned in the accounts of Humphrey Harwood in 1786. The rear shed may have opened up to create a rear porch at this time. The long front porch depicted on the Frenchman's Map may have been added during this period as well. |

Footnotes

The existence of a single chimney, together with the disposition of the original basement windows suggested that the Lewis house had been a single-room, side passage structure, and it has been reconstructed as such. From surviving brickwork it would appear that the house dated from the middle decades of the eighteenth century. Only an eighteenth-century chimney and foundation remained when the building was restored. See James M. Knight, "Lewis House," unpublished archaeological report, CWF, 1943.

Other examples of this plan-form in Williamsburg were created by nineteenth-century alterations. These include the Timson House and the Galt cottage.

That such a room could have been unheated is clearly possible--courtrooms and churches were rarely heated during his early period. At Pine Slash, a mid-century, vertical-plank house in Hanover County, the room which seems to have functioned as the hall bears no indication of ever having been heated. See Mary McWilliams, Raleigh Tavern, unpublished research report, CWF, 1941, p. 35.

Pat Gibbs was the first to advance the "building boom" hypothesis. As an example of how the rebuilding influenced local decision-making, Pat cites the will of James Shields who directed that provision for his daughters be halved to £5O each in the event the seat of government was removed from Williamsburg.

The proportional relationship of the Apollo room and the adjoining space is highly suggestive, resembling as it does, that of the Ballroom and Supper Room at the Governor's Palace. Perhaps the spaces at the Raleigh functioned on certain occasions like those at the Palace.

Until now we have all supposed that this north building corresponded with the "New Room" mentioned in Humphrey Harwood's accounts in 1786. But if Knight's interpretation of the physical evidence is correct, this structure had, by that time, been a part of the tavern for more than thirty years. Thus, while there is no reason to suppose that French soldiers couldn't have been quartered here--indeed, the inventory suggests that the room functioned as a sleeping space--we should refrain from suggesting that the room was built expressly for the quartering of soldiers.

A small but revealing representation of the tavern included in Mary McWilliams report seems to show both the shed and the northeast room in place. Unfortunately, the source and date of this sketch remain a mystery. For the plats see McWilliams, pp. 27, 30; for the sketch see materials that have been appended to McWilliams' report.

Significantly, Harwood recorded a charge of 6/0 for whitewashing "ye Daphne and New Room." For whitewashing the Apollo Room he charged 7/6--about 1.28 times what he charged for the other two rooms combined. If we are correct in identifying the space north of the Apollo room as "ye Daphne," and the space appended at the northeast corner of the tavern as the "New Room" then their combined floor area would total about 508 sq. ft. The floor area Apollo Room was about 630 sq. ft.--about 1.24 times the that of the two rooms combined. The corresponding ratios of the payments and the floor areas would appear to confirm our assumptions about the locations of the New Room and the Daphne Room.

If the northeast room was, in fact, the "New Room," our portrayal of the tavern should embrace the 1780s--the period during which the room was probably added. Since the furnishings plan recently proposed by the curatorial staff already mentions the quartering of French soldiers during the Revolution, this should require little or no adjustment of that plan.

Appendix I

| West section | 8.3 squares |

| East section (w/o shed) | 9.0 squares |

| East section (w/ shed) | 6.8 squares |

| Rear Shed | 7.0 squares |

| Apollo/Daphne wing | 23.9 squares |

| North extension | 10.0 squares |

| Kitchen | 15.0 squares |

| Laundry | 7.8 squares |

| Stables | 9.0 squares |

| West + East(w/o) + North = 27.3 squares | |

| Wray account | 30.0 squares |

Appendix II

| Period I - West | ||

| 1st Floor | 200 sq. yds. | |

| 2nd Floor | 115 sq. yds | |

| Period II - East | ||

| 1st floor | 250 sq. yds. | |

| 2nd floor | 135 sq. yds. | |

| ----------- | ||

| TOTAL AREA - PERIODS I & II | 700 sq. yds. | |

| 19 | ||

| Wray account | 780 sq. yds. | |